CHAPTER NINE

YEAR 1976

MINNESOTA

EARLY OCTOBER, and after three swift years of hitchhiking, busing, or

driving in and out of numerous states in the U.S.A., three provinces of Canada,

and half the states of Old Mexico, Shanan, now with another old beater of a

station wagon, started his third maid service, yet, during this period of confinement,

in the lake-adorned City of Minneapolis.

He had again pursued elusive

rainbows, each after the next, finding no complete satisfaction or full success

in a one of them. He had his petty conflicts along the way: in jams

intermittently in this town or that bar (fifteen different jails in nine

different states) for a battery of trivial matters, in court often, or, as they

used to say: in front of a judge more than an overly humorous chiropractor.

Nothing very serious, but Shanan did get into more unintentional trouble than a

loose puppy in a jelly factory during a midnight power outage. Regardless of

the enormous amount of world-reaped wisdom—life at every level—which Shanan had

gleaned along the way, his carelessness could have staggered the imagination of

a tachisme artist. Now, however, Minneapolis hinted at peace and was a

prime-open city, ever welcoming a wide range of innovative businesses. Maid services were virtually nonexistent in the Midwest, and the company, located in

what Shanan referred to as

his apartmoffice (living quarters and office combined) flourished from the start.

At five feet nine, Shanan was

a skinny hundred and twenty-five pounds. Yet, more than half the girls who

worked for him loved him—and frequently. He was a hundred and twenty-five pounds of

pure lust for life, a

beautiful white smile; and the egocentric word adultery held no value whatsoever. He simply floated through

destinies, aimlessly involving himself in the lives of those with which he

connected; and by whatever uncanny principle, people did enjoy his presence:

associate blindness, if you will.

“Hey—”

He, as I have previously

pointed out, had constantly labored his adult life at offbeat ventures, wrote

poems, painted, sculpted, invented strange gimmicks, and etceteras; and, while

he was running this maid service, he busied himself at the same. What is

more, he had vivid dreams as he slept, which often came to pass, and he would eagerly

replay them in vivid detail into the nearest sympathetic ear. Moreover, and now

somewhat profitably, that peaceful man’s voice from deep within—if or

when Shanan listened—would occasionally direct a more rational path.

Every project—puddle, pond,

lake, or ocean—was a dynamic endeavor, had to be swum win-or-drown, and Shanan

would paint them with glorifying words flowing ceaselessly from the brush of

his over-enthusiastic mouth, supporting them enthusiastically in his naive

dialogue of “—great potential here!” or “A vast fortune to be had!” This

attitude of explosive lusts woven into the hope-stitched fabric of all of his revolutionary

enterprises perpetually excited anyone associated with him.

Shanan had made acquaintances

by the hundreds along his meandering way, and only a precious few actually

found reasons to dislike him. The majority could still find areas of admiration

in their heart for the man, maybe because he tried so hard at his multitudinous

schemes or, quite possibly, because he was just such a klutz.

“Hey—”

He was indeed diverse, in

contrast to the norm, though if you told him, he would ebb and become

unresponsive to your voice. As I have already written, but will paraphrase

herein, he simply soared enthusiastically through his carefree life, sampling

its endless flavors among its rose-petal-garnished flight patterns.

EARLY SPRING of nineteen hundred and seventy-seven, on a dismal, rainy

Minneapolis morning, a young woman, hired that very morning and now a young

house cleaner for Shanan’s latest enterprise, brought into the office with her

a furry, white puppy with a furry, looping tail. Employee to Shanan: “Would you

mind taking care of my, my pup—just for today?” Without

hesitation, Shanan separated the wiggling pooch from the young woman’s gentle

caress, and took note of a distinguishing bodily signature. Shanan to employee:

“Not to worry. I’d be more than happy to comply. How old is she?”

“Six weeks. Isn’t she cute?”

“Yeah. She got a name?”

“We haven’t named her, yet.

We got seven more at home, but we got a add in the paper, and people are coming

over today, and we didn’t want anybody to know we got her. She’s the cutest.

We’re saving her to keep.” Shanan placed the tiny puppy onto the office floor. Instant “Snf, snf, snfs,”

little head acting like a high-speed metal detector, and a square-yard of floor

was memorized.

A chauffeur—Chuck (Chuck-Man-Jones!) Kelly  —alias Z-monster Kelly—for Shanan’s new

firm circled his hand through the lower air, wiggling four fingers high, and

motioned the young woman to exit her conversation, and get into his van. “Your

customer’s waiting,” he called out to her. Neither the chauffeur nor Shanan saw

the young woman after that day. ’Twas as if she had abruptly faded into the

Minneapolis association of the voluntarily invisible. Added to the above

mystery of the moment, the young woman had a young girlfriend retrieve her

young friend’s last, perhaps her only, paycheck.

—alias Z-monster Kelly—for Shanan’s new

firm circled his hand through the lower air, wiggling four fingers high, and

motioned the young woman to exit her conversation, and get into his van. “Your

customer’s waiting,” he called out to her. Neither the chauffeur nor Shanan saw

the young woman after that day. ’Twas as if she had abruptly faded into the

Minneapolis association of the voluntarily invisible. Added to the above

mystery of the moment, the young woman had a young girlfriend retrieve her

young friend’s last, perhaps her only, paycheck.

DURING THE FOLLOWING WEEK, having no real intentions of keeping the pup—totally

absurd, absolutely unreasonable, tush to all thought of so disgusting a

venture, Shanan, the new dog connoisseur, bought puppy food, puppy cookies, a

puppy collar, a puppy leash, puppy shampoo, puppy squeaky-toys, and walked the

little squirt as often as she required, or, as often as he could snatch her off her scrambling feet and

flip her onto the front lawn of the

kennel-apartmoffice. The company chauffeurs and the young and the older women

in the office loved the pup and showered her often with cuddling affections. On

the third day, the puppy received a name.

“Amy! (pronounced aymee) C’mere, snookies,” he

would call to her, “you sneaky lil phubby you. What’s youze lil youze doin’

now?” The fun they would have with each other was spontaneous and reciprocal

with every mutual gesture perceived by their ever-anticipating eyes,

anticipating anything moving. He would purse his lips together and make

high-pitched but short sucking noises; Amy would come scampering lickety-split

with precedential memory. Shanan figured the noises sounded like puppies

pulling on their mother’s teats, and Amy did not want her imaginary brothers or

sisters to drain the reserves. He would play this frolic-filled stratagem on

her whenever he wanted her attention. Furthermore, as the closing bell of each

day began drawing sleepy thoughts to sleeping quarters, he would allow Amy to

crawl onto the floor-level mattress and between the covers with him, whenever

she so desired. She would sneak in—for the fiftieth time—lick his face, with

her little, pink tongue; she would sneak out again. Sneak, sneak, sneak. Always

sneak, sneak, sneak. He would roll Amy onto her back and wrestle with her

beneath the ceiling of his chest; and he loved her puppy antics and her playful

defense. Amy’s feelings for him were as mutual as the color orange is to a ripe

orange; and, as she grew (or, with better context: as they grew collectively),

Shanan would qualify her ears proudly to his friends.

“They stand perfectly,” he

would boast. “I’ll bet she’s got a mix of Shepherd in her. Ain’t she a beauty?”

She was certainly a beauty,

and just as independent as he was; and though she chewed on half the items in

Shanan’s abode, he still

acquired a staggering fondness for her, and she forever loved the chase.

Amy was the first full-time

companion who truly loved him. Every belonging and every human being joined to

Shanan’s days were always temporary: Things came; things went. Evolving

from the consistency of this lifelong pattern, his pet theme on life had become

wholly wrapped into this standard and often-used motto: “I’m temporary!” Now,

however, here was a friend, and the word temporary (though in these

ultramodern but Last Days of the original twentieth century a rarely used

adjective), all but dissolved from Shanan’s vocabulary.”

Amy, a dog, yes, but a dog

with the truest effect of life itself springing forth joyously from her

penetratingly sparkling winks, would go everywhere and anywhere with her

beloved person. By the end of six carnivorous months, she was fully grown

and fattening, with the

biggest and blackest of eyes, which could steal

the stony heart from a leering gargoyle, and, which contained a variety of

tender emotions rather human in quality. On odd occasions, alas, Shanan would

have to leave Amy locked in the car, windows cracked open an inch, more or

less, and this would wrack

his compassionate conscience. Excluding those few isolated affairs,

Amy was eternally by his side. They were pals to the end.

A LATE WEDNESDAY EVENING

THERE

WAS SHANAN,

seated, relaxing

lackadaisically, and quaffing a Bud-Stupor

Beer near the front-window-end of the long bar in the old-world-styled Oval

Table Restaurant: a routinely visited and favorite upper-class suburban

nightclub, which he enjoyed with many good friends of same pleasures, including

Chuck (Chuck-Man-Jones!) Kelly  —alias

Z-monster Kelly. The customer to Shanan’s left

happened to bend to the floor, for a dollar he had dropped, but popped up as if

performing a physical impression of a medieval catapult; and, as his face shot

over the level of the bar, exclaimed with a vociferous shout to everyone in the

place: “He’s got a dog in here! Shan’s got a dog!”

—alias

Z-monster Kelly. The customer to Shanan’s left

happened to bend to the floor, for a dollar he had dropped, but popped up as if

performing a physical impression of a medieval catapult; and, as his face shot

over the level of the bar, exclaimed with a vociferous shout to everyone in the

place: “He’s got a dog in here! Shan’s got a dog!”

Carlos, a giant of a man, the restaurant’s half-owner,

ambled slowly down the meager bar.way and stood before the

new dog administrator. Searching Shanan’s eyes, he placed his fleshy hands flat

upon the surface of the bar. “Shanan,” he uttered in a monotone, and with a

strict contour to his face, “—youuu can dooo no wrong!” grinned, shook his head

jovially, and turned toward the cash register and respectably-stocked liquor

shelves dressing the lower third of the full-mirrored wall. From the stainless

steel cooler, Carlos raised an icy bottle of Bud-Stupor Beer, turned

again, and slid the brew-gratis a foot across the bar to the front of Mr.

Greatly Relieved. Merrily humming his lips into congenial smiles, Carlos

returned to the supplying of his smooth northern comforts to the balance of his

now laughing customers.

By this time, the patrons were gaping

the bar’s length at Amy. She had completely

surprised her observers, having reached her front paws to the mahogany rim of

the bar, and now sniff, sniff, sniffing with her little, coal-button nose at

Shanan’s beer glass. Upon witnessing this waggishly unique spectacle of the nose,

the folk in the pub began to delight, “She’s thirsty, Shan! She’s thirsty! Give

that white girl a drink of your beer, you old miser!”

Shanan nodded graciously

toward his friends, smiled consent, and asked Carlos for a saucer. Saucer

delivered, drink poured, tongue-consumed to the point of totally dry, saucer a millimeter thinner. Amy

wrinkled her curious eyebrows and settled back onto the comfortable, carpeted floor. The man (the ex-catapult)

sitting next to Shanan inquired if she were friendly.

“For sure!” Chuck (Chuck-Man-Jones!)

Kelly smiled . “She loves everybody.”

. “She loves everybody.”

Assuming Chuck’s reply to be a personal

permission, the man leaned gingerly sideways

to pet the dog but shot upward again, this time impersonating a rocket launched

to the moon; and, as he ascended, banged the booster section of his head

against the bottom edge of the bar.

“Jesus, Shanan!” he yelled with a loud

voice. “Hey, Carlos…!” he bellowed

vindictively, rubbing the back of his throbbing head, “Shan’s barefooted—He

hasn’t even got socks on his feet!”

Now, the clientele, in elated

high gear, delivered a symphony of whistles and hand clapping. Carlos, with wide-open eyes, gazed in low gear toward the end of the bar. Shanan was sitting

on his soft-backed chair, with a dumb two-eggs-sunny-side-up-over-a-nose look

on his face.

Deliberate step after

deliberate step, Carlos again maneuvered his hulking body skillfully along the narrow bar.way

until directly in front of the new hillbilly.

Shaking his head, Carlos leaned way over the bar and stared what appeared to be

swaying daggers into Shanan’s large, brown, swaying eyes.

Shanan sat frozen with impish,

non-blinking eyelids. “I left them in my car,

Carlos. Heh, heh, I hate things on my feet….”

Dispassionately but cautious,

the customer to his left (Mr. Ex-Moon-Pilot) reached down and grabbed a tight

hold of Amy’s silvery, ring-linked collar.

Carlos appraised Shanan for

the length of a protracted breath, reached over the bar, and placed his right

hand gently behind Shanan’s neck.

“Shanan...” he intoned as he

puffed his rosy cheeks into small balloons and blew, “…youuu can dooo no

wrong!” and the sweet-tempered

giant broke into a laughter that seemed to inundate with a liquid form of happiness the entire establishment, until

he was thoroughly purple in the face.

THE NIGHT whoopeeed on in the now de-starched-shirted Oval Table,

and the amusements loosened to the beat of the music. Shoes were hung on the

parapets of the booths, laughter was heard from every corner, and the beers and

the mixies flowed. Amy became guest of honor, and the merrymakers loved her,

showering her with their many compliments and many petting hands. Carlos sang, and the other half-owner,

L’Ru the Frenchman, on three of his mystified

patrons, practiced his philosophical mysteries. Shanan broke an inveterate

custom, and the guests of the brasserie could not be the happier.

Embraced in the intoxicating

arms of the emancipated night, certain shoeless women, old and young,

asked Shanan to dance, and he happily danced the midnight enchantresses into

tomorrow, and frequently. The barefoot dog-lover had found his nirvana. The

population of the restaurant, including Chuck (Chuck-Man-Jones!)

Kelly? Well, I hear they found theirs, too; for, if

you were to stop in for a sip of palatable refreshment today, they could easily

show you the laughter yet echoing from those noble red walls.

YEAR 1979

AUGUST-SEPTEMBER

Hurricane

David Thrashes Caribbean

Islands, New England, Violently

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA

SPRING

SHANAN HAD GROUND three wonderful years through the mill of adventure and

diversion. He had long ago sold his third maid service and began engraving

beautiful pictures onto mirrors. His endeavors in this artful capacity took him

to Chicago, New Orleans,

California, and back to Minnesota, where again tradition ruled. He tired of his glamorous occupation, not entirely

allowing its full potential to bloom (excessive glass dust in

the pores of his hands, as

he so explained, possible silicosis), and opened his fourth maid

service, but, on this engagement, in a professional office in a professional

office building. Regarding the flavors of the business, not a spice had

changed, and he still had his baby—Amy.

By now, Amy had acquired an

extraordinary routine. Whenever someone

approached her with the intention of petting or saying “Hi, Amy,” a great big

grin would spread clear across Amy’s friendly mouth, exposing a picketed row of

shiny, sharp teeth, soon known as her famous impression of a Great White Shark.

Her grin would indeed scare a timid person, but only in rare instances. Shanan,

nevertheless, would have to expound, “She smiles,” before jittery nerves

finally settled in the flesh. Amy could indubitably smile.

SIX CAREFREE MONTHS elapsed, and he again sold his maid service, this time to a

south Suburban businessperson named Tilda Danielson. Shanan made a considerable

chunk of money from the

sale and now had a steady girlfriend named Cathy James: a beautiful dusty-blonde, green-eyed, braid-haired Scandinavian

girl of twenty-six extremely blest years: Shanan’s tastes were nothing

less than impeccable. If, on the other hand, Cathy were simply a result of

supernatural luck, I would be more than happy to finance Shanan’s chances for

ten decades in Las Vegas—with my eternal soul!

Together, Shanan (and Cathy,

a young woman who was just a tad religious: Everything was always going to be

everlasting) rented a tiny house at the end of a gravely cul-de-sac

in the countryside area of Minnetonka, the wealthiest suburb—in those days—in

the state of Minnesota. Their rented house, needless to say, was not in the

midst of luxurious mansions. To show a clear relativity here, they

referred to their charming residence as The Little House on the Gravel Pit,

all four rooms of the place, plus bathroom. Moreover, its owner had had the

northern end of the house built cavernously into the side of a small hill,

hobbit-style. Nonetheless,

the pair loved their quaint, cinderblock home, occasionally invited company for

music and chats; and, the vast and endless fields decorating two

horizons of their chateau-unroyal allowed affectionate Amy a

sprawling amount of nomadic freedom. Adding to

her newfound liberties, with a couple of neighboring canines, Amy eventually made—new friends!

The money Shanan

received from the sale of his business would see them

comfortably through the winter.

’TWAS A MEMORABLE AFTERNOON, not long into the freezing and snowcapped months of Minnesota’s winter, twenty-nine days below

zero, when Shanan was hit with a brainstorm, which overrode all the brainstorms

he had ever brainstormed in his life.

“I’m going gold mining!” he

cried to Cathy. “I ain’t ever gone gold mining. I know they haven’t quit mining

gold—I just know they haven’t! I got a feeling down in me bones, see? Yas,

suh...!” With these words yet lingering in the room, he bounded through the kitchen doorway, to his

automobile, warmed her for an entire minute, and raced wildly off like a star contender at an international speed contest, into downtown

Minneapolis—straight for the main library.

SEVEN THAT ICE-CAPPED

EVENING, Shanan came pealing into their driveway and made a fast— “I’ll

be right back!” Excuse me, two fast

fumbling, stumbling, and mad-dashing trips into the kitchen, wherein the new

John Augustus Sutter scattered twenty-four books across the table. Cathy simply stood near the door, with her beautiful Scandinavian-green eyes following Shanan, mutely.

“I had to go into the library

twice, honey.” Shanan panted, huffin’-and-a-puffin’. “You could only leave with

twelve books at a time, and I couldn’t leave without all of them. People are

out west today as sure as I’m standing here, honey, —goould mining! Folks!

Folks, I tell ya! Folks gold mining! I already read boo-coo pages in these here

good ol’ gold mining books.” He threw his head back in praise, peered through

smiling lids at the ceiling, and exulted loudly. “The West is loaded with the stuff!” He threw his head into a hanging surrender, and

shook it. “Whew!”

By now, Cathy’s dimples were

showing, as she squinted, and crinkled her shoulders. With the corners of her

mouth tweaked up, she quizzed in an evocative tone, “I suppose you’re going

gold mining right this second?”

Eyeballs out exercising. “Not

right this second, honey. I’m going to read these first until I suck in a ton of this

knowledge. When I’m done with them, I

might go.” As though he were king before a pie of four and twenty golden birds

of destiny, Shanan sat himself respectively before his task of a thorough

plucking.

Cathy knew, however, no

“might go” existed within his elated bones. His methodical heart was set:

immovable as the granite cornerstone

of the first Chase Manhattan Bank. His departure was naught but a matter of implosion.

THROUGHOUT THE FREEZING

MINNESOTA WINTER, both days and

nights, Shanan hardened himself to the task of reading and learning. He nailed

gigantic sheets of paper and maps onto half the walls in the house, made

innumerable notes, penned parallel lines and countless characters onto charted

graphs denoting every occurrence of gold ever recorded in the history of every

gold-bearing state in the United States of America, and, in the exertion, had

discovered three major gold belts spanning the country from the East Coast to

the West Coast. Connect the dots was back in style.

The excitement brewed, now

bubbling within his jubilant body was interminable, to say the least. As he

pounded his studies, his fervent soul drew no pity from the man wearing it, and

he drove his eyes relentlessly over the endless lines and sentences paving the

ageless, printed avenues of his twenty-four books. The countenance of his round

Little Ben clock was manifesting its seasonal transformation; Mother Spring was

thawing frigid Mr. Winter; and every word ever darting through Shanan’s excited

mind, or fleeing from his rapturous mouth, alluded to “Gooooould mining!”

Amy herself could sense her

master’s bloating fascination instinctively, with each little sniff, sniff,

sniff of her nose. Upon entering their arms-open-wide house from a daily romp

in the crystal-white snow, she would prance her crystal-white body immediately

to his side, smile, and eagerly wag her tail, as if wanting to help him move faster—and

faster and faster he moved.

“Eeyow! There must be tons of gold in

outer space,” he blurted to

Cathy one evening. “The books say you usually find iron wherever there’s

gold.” Cathy did inquire the deduction. Shanan did bug his eyes and did explain: “Because

meteorites are usually made of iron.” Cathy did twist her lips—to the far

side of her face.

Shanan, still and all, had

his old peculiar quirk: When the flesh of his body had finally wearied from the

towering alp of his studies, just before giving serious consideration to his

beckoning mattress, he would relax himself into his huge easy chair and write

slowly until a whimsical or heartfelt poem had fashioned itself onto his thick, ruffled tablet.

If he missed a night of writing a poem, he

would diligently compose two the next, even if he had to scribe until he fell

into slumber. In a way, he was a man of habit, actually, six habits total: Amy, gold mining,

writing poems, cigarettes,

a six-pack of beer every night, and—frequently!

YEAR 198O

MINNETONKA, MINNESOTA

EARLY SPRING

THEIR GARAGE SALE was a fabulous boon. Shanan had finally returned the gold mining books to the

library, sadly but obediently, and the possessions he had acquired

during the past year, including bedroom and

living room suites, were now scurrying off to their various new homes,

excluding, of course, sundry items relative to mining and living in the

wilderness. He now had a pocket full of cash and a station wagon stuffed with a

canvas and vinyl tent and essential camping gear, packed to half the heights of

its foggy windows.

The month prior to the sale,

and energized to the brim of his ball cap because of the radically escalating

gold prices (roughly eight hundred and fifty dollars per ounce), with a glass

pie dish, Shanan had clumsily tried practicing the art of gold panning in the

nearby icy Minnetonka Creek—but to no avail. “My fingers couldn’t get used to the

freezing water, Cath…” Translated: “I don’t know a darn thing about gold

panning.”

Fully cognizant that his present mining

equipment would definitely have to be

subjected to modern advancements, after executing a thick yellow list of

telephone calls, Shanan at length found a shop in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where they retailed genuine steel gold pans, and bought two: a sixteen-inch for Cathy

(if he could coax her to

accompany him), and a king-size eighteen for himself. Furthermore, suspecting the better part of his labors

would be directed toward gold mining, he mailed his poems back to his mother, in

New York.

THE NEW GOLD MINER moseyed into the kitchen and studied Cathy. His imploring

her to go with him had increased as the long, white winter drew to a close, but

Cathy had hesitated. Shanan loved her so and desired her to be with him on this

new eternal adventure. Now, he knew the last match had to be lighted. Aware his

gold odyssey might be lonely without human company, he knew of no alternative:

He needed to propose marriage.

“You wanna poop off logs and

eat bunnies with me for the rest of your life?” He looked at the floor,

shuffled his feet.

Cathy crinkled her shoulders,

placed her hands on her hips, leaned forward, cocked her braided head, deepened her eyebrows, wrinkled her nose, puckered her lips, and whispered, “You saying what I think you’re saying?”

“Need I speak again?” he murmured,

inspecting the floor, still shuffling his feet

around their kitchen.

Cathy had planned to room with a

life-long friend after Shanan had left, but this…this was a fatter

cow of quite a different pasture. Not uttering

a sound, she grabbed her meager belongings quietly into her arms, and was

standing beside their modern-day covered wagon before Shanan could turn his

head.

“Well,” she hummed

euphorically, “how long are you going to stand in the doorway?”

Cathy was not exactly a

stranger to gold mining scenarios. Her grandfather lived half his life in the

western wilderness, applying himself to the same. He was from a long line of

rugged men, including the James Brothers: Jesse Woodson and Frank. Cathy’s

father was named Jesse Edward Frank James, so as he matured into adulthood, he

could choose from that menu of monikers the name he deemed would bestow him the

sincerest of honor. Half way through grammar school, he decided prudently one

day, having duked it with half his school class and half the rest of half the

other classes, the name Eddie would be just what the doctor ordered; and,

coincidentally, the doctor had. Nevertheless, regarding gold miner grandpa, Cathy’s grandmother had left her struggling husband in them thar hills years

ago, to raise their children near the readily accessible conveniences of the

city, where creature comforts were easier to find. Although Grandpa James did finally make a fortune in the West, discovering

a wealthy talc mine, grandma James remained in

the city, staying close to her developing brood. Be that as all this may,

however, Cathy was confident she could tough it; and, cooed by the fiery

speeches of riches and independent happiness pouring off the tongue of her everlasting

beau made the entire enterprise all the more glamorous and appealing, and more

appealing, and more appealing….

“C’mon…Amy,” Shanan cheered

loudly. “Youze lil youze has gotta jump in, too.”

A long, embracing kiss did

our advocate of the gold pan plant upon Cathy’s like-minded smile. They joined

lively Amy in the front seat of their four-wheeled relic and began driving

casually outbound from the cul-de-sac and into their ultimate choice, a

multitude of tiny clouds of gravel dust twirling gracefully from the breezing

air trailing their vehicle. Thoroughly encased within their delighted hearts

was also twirling a jewel-studded memory of nine cuddly baby puppies (adopted

optimistically to nine forewarned households) that “affectionate Amy” had given

birth to during her brief stay in the little house on the gravel pit.

BIG BAR,

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

SILVER AND GOLD VALUES WERE

SOARING throughout the world. Shanan,

acting on an unanticipated tip from an attorney in Minneapolis, finally

appeared in the Trinity River town of Big Bar, California. Canyons of California’s Trinity River

were swarming with

broad-striding feet and their high-spirited owners— impassioned men and their fiery women, from half the

United States and half the

country of Canada. Gold-related pandemonium

kindled itself anywhere a man could drive a questionable stake. Shanan’s fever,

likewise, with respect to the yellow metal, was by no means unique, as this

phenomenon was equally exhibited by adventurous gold explorers in the locales

of every modern gold bearing area—desert, mountain, field, or stream in the

country, if not the world.

The old federal mining laws

were meaningless to the men of the golden gleaning, and claims were being

double- and triple-staked as though tomorrow had fallen victim to a

pre-embedded x-mark on the

war calendar of eternity.

Gold dredging was by far the

fastest, yet not the easiest, method for recovering gold from the rivers and

creeks. A man could drive State Highway Two-ninety-nine a solid twenty miles of

the Trinity River and observe nothing but miners hustling and bustling about

and diving for the riches of their dreams. The holes they bored ran from a

variety of simple and unassuming ditches, to immense and complex funnels

drilled down through the sand, rocks, and boulders (overburden) until the hole

exposed the river’s bedrock. If blest fruitfully, the diver or divers would uncover

bean-sized and possibly larger pieces or nuggets of gold long-hidden below the

sand, rocks, and boulders. More miners than fewer, lamentably, were not thus

blest. All the same, during exceptional occasions in the Trinity River, as in

many rivers, as a miner gold-dredged himself into the mansion of his

imagination, fine flood-gold would run with the overburden from its loose top

gravels down to the hardpan (compacted blue clay); and, after that, the

bedrock. “Eureka…!” These types of glory holes paid handsomely, but to refer

them as scarce would certainly be an understatement.

At this unpromising juncture,

you potential gold enthusiasts out there might be considering canceling your

order for that new gold mining book or shovel or steel pan, but allow this

writer not to dash the eternal inspiration into oblivion. Gold was indeed to be

found and, often predictably, in exciting and serious quantities.

Sixteen-year-old Elmo, son of John Spool, dredged sixty thousand dollars’ worth

of the amber-colored element in less than a week, and hit the road after six apprehensive days,

heeding a well-founded proverb from San Diego Rick, a well-seasoned diver,

gem-hunter, and miner: “Hit the road, Elmo!”

San Diego Rick was a tried and true

friend of Shanan’s. Elmo, though only sixteen years of age, blew

them thar hills, because of potential adverse

repercussions from his dad. Elmo had pestered for two unbroken weeks on a hunch, “Move the five-incher

behind the huge boulder at Big Flat, Dad!

Let’s move the dredge. Gold’s gotta be a natural on the down-side of that rock,

Pop. I just got a feeling!” At the end of those two weeks, Elmo’s father had

given him the five-inch dredge, told him to remove the dredge and

himself from their camp, and, “Don’t ever come back to this camp, you hear?”

John Spool kept the six-inch dredge for himself and just managed to keep

soul and body together.

Five extraordinarily scenic,

yet mountainous winding miles upriver from the picturesque hamlet of Big Bar,

Truman White (a stocky six-foot-two red-bearded man, who loved the world, and

always had a smile for his neighbors) and Truman’s easygoing partner, Steve Rillsby, brought in nearly two ounces of gold per day with their

eight-inch dredge…on days they worked. “What the heck, at eight hundred dollars

per ounce, in the middle of paradise…?”

Gold miner Rob Boar (who

became a very close acquaintance of Shanan’s), and Rob’s older gold miner

brother, Anti-Forest-Ranger Earl, had a countywide reputation for prospecting

and hitting major jackpots on a monthly basis with their eight-inch

dredge. They typically had a canning jar or two filled to the brim with large and small nuggets to

display to curious “close --- friends.” The

two of them, though on different claims, dredged holes so massive a man would

doubt that the following spring runoff could ever fill them again, but it

did—with ease.

Nonetheless, violent and

whitecapped river flooding spawned by a snow-loaded winter, an early thaw, and a

long and hardy spring rain dumping into and churning the Trinity could roll a

small pickup truck a mile or two a day beneath the stampeding, sea-fated waters

without ever flexing a muscle. During this type of runoff, all of the holes the

miners dredged refilled, and a prospector would need God if ever to find those

same holes again. Those old digs were often carved into the river again and

again; and, after a miner (and not necessarily a novice) had poured his guts

and labors into an entire summer, he would feel like shooting his equipment, or

the poor, lonely man who moved back to his granny’s farm, the poor, lonely man who

had originally sold him that worthless patch

of gold-free and Volkswagen-sized boulders in the first place. Gold often runs

in shallow waters, but not often in shallow hearts.

SHANAN did not categorize himself as a beaver: “I don’t have

enough money to purchase dredging equipment,” and opted for the above-water

gravels and boulders, which, in the Big Bar area ran everywhere along the banks

and shallows of the river. In this free-and-accessible material, he would do his prospecting. In special areas, he would dig extensively into the submerged river

gravels located near the

shoreline; and, after a month of tedious “Hmms”

and explosive “Wows!” he learned how to spot the more logical locations in

which gold potentially settled. He was now (as they used to and possibly still

do call them) a gold-sniper. “And a dad-blamed good ’n, too! I can smell the

stuff.”

Shan…

Kram Engineering was at

present in the forefront of dredge sales and recreational mining equipment but

way at the bottom in qualified gold-miner ratings for safety features and

worthwhile gold-recovery. Unfortunately, greenhorns knew nothing of the various

dangers associated with mining equipment and often died in the learning. A

French-Canadian named Jacques Bossuet had allegedly died from carbon monoxide

fumes belching into his air regulator from the exhaust system on the engine of

a Kram Dredge he was operating in the Trinity River. Stories of similar

calamities were drifting anxiously up and down the rivers of the golden hope. With Shanan mindful of these

controversial tragedies and overtly disgusted

with the unprofessional mining assistance offered by those claiming to be

expert in the field, and the back-woodsy mining practices still employed (and suddenly nurturing a desire

to own a five-inch dredge for himself), the invention genes in his blood moved him to design on paper a triple sluice

box, advanced, for the dredging industry.

Concerning his unusual

apparatus, Shanan telephoned Jufus Kram, owner of Kram Engineering, explained

the idea, and inquired about Jufus’s future dredge designs. Kram told him there

was nothing on the table, but if he liked Shanan’s designs, he would assuredly

give him a current floor-model five-inch gold dredge in return for the efforts.

These words were sufficient for correcting and fastidiously drawing the

hydro-mechanical design and testing it successfully, but to a limited degree.

Along with high hopes, he sent his plans to Kram and waited impatiently for his response.

Three high-expectation weeks

passed, and Jufus wrote he was not interested in a triple sluice. This confused

Shanan and broke his heart, for he had proven beyond a headshake that with a

triple sluice box, properly assembled, the extremely fine gold would not escape

as easily during operation as it did in the latest Kram dredges. He was also convinced gold

miners would be thrilled with a product that

would increase the weigh-in of the golden flakes by the end of the day. The

pros (who, when affordable, preferred a Spokane, Washington, Jim Horan

Precision Dredge) were well aware the big money was always dependent on the recovery of the finer gold, Horan’s personal principle in the construction

of his product. Among the

more successful operations, the abundant fine gold (specks and flakes) would

pay all the expenses—dependably. The nuggets,

when or if ever uncovered in the dig, as a rule became jewelry or high-priced

specimens: rewards and

natural trophies of the game.

Two months progressed somewhat serenely, but a providence-powered peek

in a California mining magazine revealed Kram’s New Triple-Sluice

Five-inch Gold Dredge, and at triple price. This news was upsetting enough to

ripple his skin, but the day Shanan saw a factory released model of the new

dredge on the Trinity River (the triple sluice arrangement a near reproduction

of his own), the contents of his stomach wanted to do a high-dive into a

bucket. Even after all of this corporate exploiting (as Shanan perceived it to

be) of his mechanical and hydrodynamical talents, believing there was still a

chance for remuneration, he tried telephoning Jufus Kram, and to offer

technical assistance, surprisingly, but with no success; Kram simply ignored

his calls, delivering not

a penny’s worth of gratitude to the initiator of the contrivance.

The only mental relaxant for

Shanan: He had held back his critical riffle design arrangements and water-flow

plates, and the new Kram was a virtual dud. Gravel that was dredged into the

sluices accumulated quicker and smothered the riffles in a blink and a half,

and the gold retrieval capability of the new machine was no better than last

year’s model, if not worse. The fine gold still blew straight through the

sluice, and the miner ended his day having to separate three times the amount

of dredge material. Nevertheless, trusting gold miners (witnesses to history)

stood in line for the innovative machine and learned the hard way, like Shanan:

forever learning the hard way. He used to speculate whether the day would ever

come in which he would find “…an affluent corporation who would compensate (or

who gave a damn about poor people on government food stamps, who handed their

ingenuity naively to them on a regular basis—But, hey, chump.” he would muse consolingly out loud at

intervals of self-punishment, “that’s life in

the big nursery….”

MEANWHILE, BACK AT THE RANCH:

THE

THREE SALOONS

sharing the Big Bar / Big Flat areas were—when

it came to push and shove—jostling, bustling, and rowdy, and a fight or a

weighty dispute occurred im.practically every other night. The

twentieth-century gold camps were just as wild and unpredictable as the

mad-dash nineteenth century camps of risk-taking glory, and the incontestable

lust for the color was emphasized, once in a blue moon, by a stray killing.

No specific laws governing current

mining activities were in force, and whenever a personal mining feud

surfaced between them gold-panning hard-jacks, the California Fish and Game

Control and Forestry Department’s hands were tied—circumstantially tied—“Go

find a judge.” The miners enjoyed nearly total and unrestricted freedom. The

law hid frustrated in a far corner of this uncivilized garden of passions; and

half the miners, including their women, were carrying guns, concealed or

brazenly unconcealed—at their sides or in easily excitable hands.

Shanan owned two guns: He had asked Cathy if she would purchase an AR-7

Survival Rifle in Minneapolis, and could soon shoot the flame off a candle at

fifty feet. Hip-blasting beer cans off the ground at thirty feet came on as

second nature. Cathy shot as if she were born with a machinegun in her hand.

Shanan again asked her to buy a used .38 pistol, shortly after arriving in the

historical gold mining town of Weaverville, California, Route Two

ninety-nine, (approximate number of families: fifteen hundred and two;

approximate population: thirty-three hundred and seventy; roughly twenty-five

hundred and twenty-four paved miles from Washington D.C.). Shanan wanted to be

ready for whatever came along in them thar hills.

Twenty-four miles of winding

mountain state highway west from Weaverville was the evergreen-studded mountain

community of Big Bar (One general store, a tiny post office, a saloon, a cafe

with gasoline pump, and a Laundromat). At the tree-shaded and cost-free Big Bar

Campground (fourteen-day limit) near the eastern edge of Big Bar, across a narrow

bridge from a national forestry station, Shanan and Cathy finally prepared

their dual-tented camp and future plans for their gold explorations.

WEAVERVILLE, CALIFORNIA

POLICE HEADQUARTERS

WEST EDGE OF TOWN

’TWAS WAS A BEAUTIFUL Sunday afternoon. The Weaverville Chief of police had arranged a special

meeting for a new-weapons demonstration, and every off-duty

police officer, sheriff, and state trooper,

uniformed or otherwise, in the county was attending.

“This, gentlemen of the shield,” the

grinning Smith and Weston representative declared, rather

officially, “is the Glazer. The Glazer is a

bullet. You will find no other bullet like it in the world. The Glazer is a

killer. The Glazer is used only to kill. Anywhere it hits a man, the Glazer will kill or

permanently disable. The Glazer is a miniature A-bomb. The Glazer is a

hollow-point model, and its lead slug is

filled with liquid Teflon and micro-B-B’s. A grain of patience, my friends, and the rest of

this show will amaze you.…”

An intriguing form of

anticipation was felt silently among the officers, having no idea what to expect next, as they

fastened their eyes on the bullet in the salesman’s hand. The mood now

spiced suitably, the rep drew a pistol from

his black,

crisscross-stippled holster and fired angularly at a concrete pad prefacing a sheet of unused plywood leaning upright

against a post twelve feet away.

“Note...the plywood.” The

S&W representative stood with his outstretched hand motioning elliptically,

referencing the entire sheet of plywood. The officers stepped cautiously to the

board, examined it thoroughly, but could not detect a scratch. “The Glazer,”

the rep went on, as his gaze and voice traversed the distance of the walkway to

the police officers, “is designed for metropolitan use. You can shoot them

downward, and they will not glance off the pavement. This is a built-in. In the

event of pedestrian presence, virtually no chance of friendly injury or accidental death can ensue, unless a pedestrian slips literally into the path of a shot. The Glazer

is manufactured for .308’s, down to .38’s, and

can, believe it or not, be produced for .22’s.”

Further incentives or

demonstrations, though there were more to come, would be unnecessary. As far as

these law officers were concerned, they now considered their current gun

ammunition obsolete and would assuredly want to add to their arsenal a large

assortment of these remarkably effective bullets.

“As I told you awhile ago, gentlemen,” as the law

enforcers retraced their steps, “you’ll be amazed at what the Glazer can do.”

The rep uncurled and wiggled a thumb-up to two assistants standing by a target area in the open-air firing

range. “Okay, boys, do your duty!” Upon receiving the signal, they nodded

and lifted a broad, black cloth covering a large, fresh watermelon resting atop

a crude wooden workbench thirty feet from the salesman. At the completion of their task, the two men returned

to the frontline. The Smith and Weston man raised his gun, took careful aim, and shot once at the melon. “Follow

me, gentlemen.”

As the rep had directed, the

men of the badge walked to the end of the firing-range and gathered at the

tabled watermelon.

“Please note,” the rep

instructed, squinting toward his green but motionless victim, “the bullet hole

going into the melon. You can

hardly see it, am I right? Now take a close gander at the other side of the melon.”

The officers inspected the

entire melon, heads bending down toward it, ascending from it, eyes peering

around it. No other hole was visible except that which was shot into the front

of the melon. A barrage of questions began to rise from curious throats, but

with a high-and-winding twist of his hand, the arms salesman interrupted—

“This—is the Glazer at its best. And for the weak of stomach, I suggest you

ready a barf bag.”

The sales agent lifted a

bulky, sixteen-inch perforated kitchen knife off the table and sliced the melon

deftly down its middle. The melon tumbled open, and both its sides wobbled

precariously toward edges of the table but did not fall to the ground. The officers stiffened in unbelief. Nothing

more than a thin residue of pink mush remained inside the cavity of

the gutted melon, altogether annihilated, its fragrant shell now a mere quarter

of an inch thin.

The demonstrator smiled at the astonished faces of his

highly impressed audience. “If the culprit is hit in the guts, the result is no

different from removing the stuffing from the center of a rag doll. As I stated

before, gentlemen,” the man reiterated: “The Glazer is a miniature A-bomb. When

this superior example of weaponry enters a man, it leaves nil to be desired—especially at the autopsy. And, by the way,”

he concluded, “the gun I was using?” with a grin, “This lil ol’ Smith and

Weston, model forty-three .22 caliber!”

“Just what we need,” a huge, redheaded

officer sneered openly, bouncing a couple of

sample Glazers in the palm of his left hand. “With the garbage coming into our

hills these days, we could each use fifty cases of these little

mothers.”

THE

avant-garde, pleased by the

representative’s gratuitous gifts of a promotional supply of product, and his

parting remark of “ten percent off the first purchase,” disassembled and headed

composedly to their vehicles. “You sure wouldn’t want to use this ammo buck

hunting,” a trooper chuckled toward his fellow officers: “The only thing you’d

be putting in the center of your supper table would be a three-foot-wide hole.”

BIG BAR, CALIFORNIA

THERE WAS SHANAN, and it was indeed a beautiful Sunday afternoon. He and

Cathy were two among a wily bunch of other land and shore miners, carving their

prospective destiny from the landscape of Ingot’s Bar—a state-operated,

roadside rest and picnicking area nestled beneath peaceful pines by the Trinity

River, four miles east of Big Bar. The serendipitous

crowd was totally absorbed in their digging and panning for loose gold they

could snipe from the abundant and thick-tangled roots of water-shrubs or weeds

or bank mosses or the boundless gravel deposits. Everywhere you spied, steel

shovels, iron picks, and alloyed spades were raising and chunking eagerly into the waiting ground at an uninterrupted pace. Men, women, and a collection of

their children hunched near to the earth and close together, their darting hands and variant tools

cracking open ancient reefs of rock crevices

and whiskbrooming the bared prehistoric or redeposited contents into their steel gold

pans—inside-bottoms purposely rusted for optimal attraction of the gold—were becoming

indescribably exultant!

Between their hard-earned,

well-spent breaths, the hopeful and young prospectors would buzz jubilantly the

highest of their prayed-for expectations to one another, “Baby, this pan’s

gotta be loaded!” Pulverized dust and gravels nesting on exposed bedrock were

broomed painstakingly into waiting steel gold pans, and a small army of knees

was bent along the swift river’s edge, balancing their Pollyanna owners as they

shook and washed their gravels gingerly down to the black sand concentrates.

Swirling the water over the blacks until those tiny golden stars lit up

Heaven’s side of the pan would give birth to a feeling only a first-time gold

miner could share within himself. Shanan and Cathy had worked vigorously at

opening a hole for three long days, and now had it seven feet wide square by a tapering

six feet deep, located conveniently not a

stone’s throw from the picnic-tabled rest area. None but this cranky old

gray-haired local whispered his bitter displeasure. “I should call the damned cops!”

The miners of the eighteen

hundreds did not bother with the minuscule gold the above-mentioned parties

were getting. Thus there was enough fine gold in the ground for every one. Many

of the above-mentioned parties, however, abandoned Ingot’s Bar because of lack of knowledge in

amalgamating the fines, spending more than a week in gleaning only an

eighth of an ounce of color, or had left for what they believed to be richer neighborhoods,

and there were many of those.

Paying no mind to state or national

laws, or a cranky old gray-haired man’s

personal displeasure, Dang…! Shanan thought, all of his senses confirming the reality of

the moment: Gold truly is here.

“No denying it, honey,” Shanan mused elatedly and out loud to Cathy, “this is the only life…!

A RETIRED GENT who

had prospected those hills in the mid-nineteen-forties had taken young Bin under his wing and had

schooled him in the rudiments of his new trade. Hence, before the

chickens were fully awake and producing

proteinic ovals, our miner of the gravels had perfected the finer art of gold

panning. Again, it was true, just as true as it is today (verifiably speaking)

gold does exist in them thar hills; and, gold will abide in them thar hills for

as long as gold abides anywhere. Furthermore, impossible as this may sound, Shanan and Cathy were

offered the opportunity to rent a grandfathered-in trailer; and,

whether you’re able to fathom this,

they paid only fifty dollars a month, no utility or telephone bills, and the landlords, Ernst and Shelana

McKinley, would accept gold in place of

cash—at the drop of a hat, and allowed them to use the outdoor, extra freezer, which did have electricity.

The trailer had no electricity (though

it had outlets) or running water (though it had faucets).

Regardless, for the gold mining pair, the trailer was a mansion and a

miracle; and, well before Daylight had crawled herself over the blues and

greens of the Pacific Ocean, the happy couple

was moved in and cooking on the top of their kerosene heater. In contrast with

their first sixty-seven days in campgrounds and a ten-by-fourteen tent, and suffering twenty-nine of

those groundbreaking days in a perpetual spring downpour, the trailer proved a genuine utopia to the twosome. As a

finale to the trailer-decorating week, after receiving welcoming consent from

Ernst and Shelana, Shanan affixed a heavy-duty extension cord and a water hose

to complement the trailer.

Ever so weary of the persistent rain

and the varmints, they now discovered the vast

difference between a thin canvas and vinyl tent in an abandoned creek-side

state campground and a

solid sheet-metal trailer. On top of which, their gold miner’s trailer had real cupboards—covetous high and low

cupboards.

A

retrospect

During Shanan and

Cathy’s tenting days, and their ever-developing chapter among the gold

camps of California, after moving from the

cost-free Big Bar Campground (the free fourteen days having expired) and

establishing a new camp at the free Big French Creek Campground (no day-limit

imposed, abandoned by Forestry personnel, due

to a severe lack of state funds) at the edge of the rippling Big French Creek, their seven- by seven-foot supply

tent contained cardboard boxes instead of cupboards. Unlike the trailer, the supply tent had undergone an incessant

plague of mice, and Shanan and Cathy’s

daily provisions had fallen to infestations at various and distressing levels of unpleasantness. A day of deliberating gravely over this predicament moved

our local inventor to grab a rinsed plastic one-gallon milk jug, pour

three inches of water into it, and smear peanut butter onto the insides an inch

below its mouth. With this accomplished, Shanan placed the milk jug five feet

from the supply tent and balanced a piece of split wood from the ground to the

jug’s neck, an angle not unlike the hour-hand of a wind-up clock at ten after

the hour. The following morning, seventeen

drowned mice were in the milk bottle. The next sunup, in another bottle,

the last nine had met their, as Shanan described it, “watery de-mice.” From

that two-day episode and thereafter, the

unique trap stayed absent of mice, as absent, finally, as the duo’s

canvas living quarters.

With

their comforts secured impeccably,

Shanan and Cathy, having completely finished their trailer remodeling and

reconditioning, could now concentrate hours of sun-filled venturing,

prospecting the endless banks along the Trinity and other Rivers, and creeks,

in diligent search of the elusive color. They filled their pans and sluice at the river’s edge,

making withdrawals from—those banks; and at

eight hundred dollars per ounce, they did well enough.

The Big Bar general store, gas station, and cafe also

acted as trading-post banks and had scales for weighing gold, in exchange for snacks, petrol products, and suppers, and

everyone prospered thereby. Life in those thar mountains had not changed

since the gold rush days had screamed through them in the second half of the eighteen hundreds. Back in those half-forgotten

days, your run-of-the-mill gold miner was usually tapped of legal

coinage and, brining us forth into these

days, so was Shanan. On the other side of

the coin—government food stamps, a fast odd-job-twenty-dollar bill here

and yonder, and peddling his gold off countertops at a handful of general

stores throughout those northwestern hills came in mighty handy. He was hardly

ever without his beer and cigarettes. This entire semblance was, as they used

to say emphatically, “Nawthin’ short o’ Paradahs.”

I mean, let us scrutinize Shanan’s

whole-case scenario for just a moment here:

the slickest “good ol’ dog” on the face of this spinning Earth; a couple of

accurate guns and free venison; fish poles and the best trout holes in the U.S.

of A.; long sunny days; warm and brief winters; food stamps; beer; cigarettes;

a steel gold pan rarely hungering for the color; fifty dollars monthly rent; no

visible sign of conscience, and a lonesome young woman who could verily inspire a new national

anthem! —So, who would want to die and take a

chance on Heaven!…?

SHANAN AND CATHY were sniping their way optimistically along the rocky

banks of the river, on a scantily clouded but dry Saturday afternoon. For three

lighthearted hours, they had plied their talents to digging, chopping moss

(whispering their souls’ desires to each other), cracking open and briskly

dusting a slew of freshly uncovered, and only until now, unnoticed and ancient

crevices for their long-hidden treasures.

They were industriously panning the

ultra-crushed particles of dirt and pea gravels meticulously down

to the assorted black-sand and gold-blended concentrates, which

usually contained a rewarding and bountiful assortment of micro-thin

flakes and wee mini-nuggets, when, quite out of the blue, a forceful

pillar of wind raised a funnel of fine dust

twenty or thirty feet into the air. Over the past years and generally from a reasonable

distance, Shanan had seen dozens of these rascals twisting and carving

their short-lived, dusty paths through areas of dry, powdery earth

throughout the desert-country spanning the

great Southwest, and elsewhere. Dust devils were their traditional names, and they came on like

miniature tornadoes, normally harmless, but

often stretching their spiraling tentacle of sand and dust a mile or more into

the sky.

He and Cathy were as

captivated as a couple of kids thrilling at a lion tamer without a twenty-foot

bullwhip. With no apparent motive,

Shanan took a quick breath and (misty-eyed as if in a trance, and as if he had wings on his feet) glided his steps smoothly into the center of the

coiling spout of wind and dust. Within seconds, the wind ceased, the funnel

disappeared into the heavens, and vanished like a bad dream, leaving the gold

miner standing—mesmerized and shuddering.

“God, Cathy! Memory…! Memory…!” he breathed outwardly

and in absolute awe. “I don’t ever want to jump into a journey like that

again.”

“What do you mean,” she

quizzed, “‘a journey like that’?”

“I’m not positive, honey.

That reminded me of something— something weird. I don’t know if I can explain. But while I was in that thing, I felt like I was commingling with spirits of

God! You have no idea what’s going on inside them devils. Boy! Crazy…!”

Standing, yet limp with a

granite expression on his face, he proceeded to babble. “How long was I in that

funnel? Could you tell…? I couldn’t tell. But I don’t ever—I don’t ever want to

go through that again.” He began to cry. “Even though I was here on the ground,

something inside me was trying to raise itself up and out of me. Them suckers

are scary. I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody. They’re different, Cath,

different. I’ll never step into one of those things again—in my life!”

Cathy stood several feet from

her man, mute; she had no words for this. His trembling response took her

completely by surprise. She could say nothing, but only try to comprehend: He

used to be so…so durable.

Shanan was not exactly a

religious man, but this, this was a bona fide spiritual experience, and it all

but floored him through the sand beneath his green rubber waders. He was a

regular beer drinker, smoked his pot, but seldom, as it made his gums bleed,

and, before Cathy, had slept with his women anytime he had the urge.

Furthermore, fighting was not part of his makeup. On the other hand, shrinking

from a fight, as he had when he was a schoolboy, was not, either. He cussed,

but rarely. Nonetheless, this whirlwind, this whirlwind encounter, was a

spiritual walk he would remember for the rest his short life upon this Earth.

NEXT DAY

SUNDAY

THE SUN was gliding her beaming fingers of solar stimulation over

the green-capped mountaintops and warming a gentle touch round their noble

trees, through their noble branches, their noble needles, their noble

pinecones, leaves of their highborn cousins, and the peasant-like foliage,

which gathered quietly at all their wellborn feet. The glowing reach of the

foster of the hope of day also shed vertical sheets of yellow-gold rays through

slits in a miniature set of sheer curtains, half the wardrobe of the little

trailer window they now appareled. Cathy, pretty as ever a dream could be, rose silently from bed, faced

a flattened hand downward, streamlined twin

sheets efficiently from wall to wall to wall; and, as was her bright-eyed, refreshing Sunday custom,

enthusiastically prepared for a tranquil and

carefree day.

Mr. Dust-Devil-Rider,

however, already up and at ’em, developed a sudden quirk: He—made a Cross, a

delicate Cross. He tied a couple of small and dry fir-tree branches tightly

together, snapped them free of their twigs, and stuck this delicate Cross into

the soft, pebbly ground behind the trailer. If ever a particular day were

unexpected by the world, indeed this particular day was, and commencing from

this particularly unexpected day and replicated every Sunday morning

thereafter, Shanan would bow his head meekly, say a simple prayer before his

unadorned Cross, and sprinkle a pinch of fine flake gold at its pebbly base. He

figured that if God was generous enough to lead him to the gold, he would give

a smidgen of gold back to God: Maybe God’ll give me more.

HAVING NO DESIRE TO LABOR ON SUNDAYS, they

whiled the early hours with word and dice games, ate and finished a late and

lazy brunch, and attended to a light chore or two. As Noon began to stretch her

broadening shadows across the land of peaks and canyons, Shanan stood, stretched his slender arms,

and exchanged his upright position in favor of

the horizontal as he opportunely laid himself onto the bed. Cathy, swaying her

torso rhythmically to a childhood tune she was humming, wiped the knife and

swept bird crumbs off the kitchen table and vigilantly watched them cascade into a white paper sack.

Feeling somewhat drowsy herself, Cathy decided

to join Shanan in his afternoon nap. Her man was lying lengthwise upon the sheets, flat on his back, mumbling calmly, meditating, and pushing his thoughts mystically to wherever they

would carry him. Cathy loved listening to his copious ramblings, his open ingenuity, until he at last buried himself in the

numbness of his sleep. If they were driving along somewhere, relaxing over a

beer, working the gravels of the Trinity, or doing nothing but idling an

evening into tomorrow, his constant philosophizing could keep her enthralled for hours on end “Right, Cath  ?”

?”

Shanan had a kitchen-collage

philosophy on life: a dash of Christianity sporadically mixed with a spot of

will-worship occasionally blended with a grain of confused Zen mixed with a well-flavored portion of contemplation

on paranormal phenomena, strongly dosed with

chunks of shredded mechanical, electronic, botanical, and chemical disciplines,

topped off with a healthy covering of natural sciences; and, this potpourri

stew was served liberally alongside a savory helping of fine arts; and he could

feed his tasty delicacies to ninety percent of the knowledge-starved populace

within his midst, if they were not busy with something important. Identified

with the first percent of the populace, Cathy loved them by the plateful, “Right,

Cath ? A pouch of magic beans,

anyone?

? A pouch of magic beans,

anyone?

She would put his renderings

repeatedly into practice to see if anything could be gleaned or witnessed, and

the results were often storybook amazing: I can’t believe this! Bobby showed up

just as I had envisioned. All I did was contemplate the three points the way

Shan showed me. How did he learn? I couldn’t grow plants by tearing a twig off

and just sticking it into the dirt and walking away. But now, now I can, his

way. Weird! I wonder, though, if that doesn’t border on the occult. But where

does he get this stuff: ‘Aging is only brought on psychologically.

People only grow old-looking because they get more and more angry and frenzied by

this world and do wrong, not because of time and old age. Love life: Stay

young’?

Shanan’s methods (formulas on

life, fundamental principles regarding causes and effects: causes and effects

particularly) far excelled that which Cathy had previously read. If you do

this, Cath, this and that will happen. If you set her picture facing your

favorite chair, within ninety days, she’ll walk in for a visit. Hang this over

your bed, and you’ll dream of…hang this picture over your bed of this young and

peaceful woman with a peaceful baby, surrounded by peaceful colors, and you’ll

stand a good chance of getting pregnant…, “With a wee tad bit of the right

assistance, right, honey? C’mere—” “EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEK!”

An additional element did

also increase Cathy’s supernatural portfolio: She consumed many hours of

reading, especially when Shanan was at his mining. Books containing ludicrous

or profane context were against her codes of sanctity. She read the leading

scholars and thinkers from ancient to modern days; the best-selling novels;

mysteries; sci-fis; paranormals; biographies of famous lives, or stories of

far-off lands; and these literary affairs conjointly expanded her ever-widening

intellect.

When grocery shopping in

Weaverville, she would predictably schedule herself to stop at the local

library; and to return to the trailer deficient of literature would have represented a cardinal sin; and, finally (though no church existed

in Big Bar), the Bible—Cathy read the Bible. This was a wrench that

weakened the framework of Shanan’s and her

relationship. Shanan could not understand her habit. “God already sees you’re a

good person, Cath. Just thank him once in a while and say the Lord’s Prayer. He

knows you love him,” he would maintain innocently. While living under the same

roof in Minnetonka, Cathy had mentioned their sleeping in the same bed “in

sin,” attempting to sublimate Shanan’s carefree attitude toward fornication. He

shrugged off her comment as irrelevant. Now, however, this new event moved Cathy to consider a latent quality in him, a quality she had not witnessed

before: Shanan………made a Cross!

On the other foot, Shanan’s

philosophies, since the inception of their reciprocal sharing, had made Cathy

stronger: self-reliant, even assertive. Now, in her every day conversations,

she was no longer that poor little bashful beauty from Blaine, Minnesota. As a

matter of fact, often, but only when they were alone, she would wax rather

bold, outspoken, no-nonsensical, and matter-of-factly, which perpetually

astounded Shanan.

Nevertheless, her sensitivity

toward the everyday life going on around her had not changed an iota; her

homespun vernacular in the homespun quarters remained the same: “Gotta go

consult with Shelana and see if I can get that recipe.” “Gotta see if Tiana can

corn-row my braids today.” “Gotta get a letter off to Mom.” Cathy loved to

write, loved to write volumes of whatever entered her inner self. Possessed

with a remarkable penchant for the pen and the written word, she would write by

the reams, kept a large cardboard box of her writing secreted from everyone,

shut away in an ample

kitchen drawer. Cathy’s writing was her sole, personal “Mine,” and, as inquisitive as Shanan and their mountain friends

often were, no one else’s,

except for one isolated instance: Tiana’s father

had had a severe coronary obstruction, and during one of Tiana’s frequent

visits, she had requested of Cathy, “I know you write, every free minute you

have to yourself, and I’m sure your sheets are filled with spiritually soothing verses. My father’s really sick since his heart operation, Cathy, and I wonder if you

might have something in

writing that would make him feel better?”

“For you, I’ll look,” Cathy replied

considerately, “but just this once. I don’t

even let my dad, who I honor and who has his own tribulations,” she stressed

adamantly, “read my material,” firmly in defense of her literary privacy.

Still, beyond all of the above marks of manner, nothing had really changed,

except now—Shanan………had made a Cross…!

A MONTH ELAPSED, and either Shanan had over-indulged his spending on beer

and cigarettes, or the gold up at Ingot’s Bar had thinned to a level of poverty. The cupboards were bare, flood layers of gold played more difficultly, and a

substantial spring runoff would be necessary to replenish the gravels richly

enough to provide the table with even a piece of daily bread. Yesterday

they had squandered their last food stamp on a can of hash and were now

envisioning a dreary evening wherein they would have no need to scrub their teeth. Shanan

lifted his eyebrows and smiled sadly at poor,

hungry Cathy.

“If we’re going to eat

tonight, honey, we better hit the river for a mess of trout. We can’t refill

our old banana peels.”

Uttering not a single word, Cathy grabbed the fishing

rods, hyper-spaced through the doorway, threw them into Ol’ Betsy, jumped into

the front seat, and stared patiently through the front window.

Gads! Shanan thought: She

took me seriously. I hoped she’d have gone to the Big Bar Store to mooch a

couple cans of who cares what.

“C’mon, Amy,” he called

animatedly, and his smiling dog leaped confidently into the front seat with

Cathy and sat focused dead ahead, raring to fly down the road. The greatest

desire in this whole wide

world Shanan’s dog, Amy, could ever express,

and with a mere wagging of her tail—Let’s go for a ride. Next to riding: chase sticks, swim, smile, eat anything,

and certainly, of course, tease daddy.

Shanan launched himself in

behind the wheel and headed out of the earthen driveway. “You sneeeeeky lil

self you,” he sang to his

dog. “How’d you get all that fur stuck all over your sneaky lil nosey?” Amy just turned her head toward him, eyeball to

eyeball, as if she were sending a message: ‘Try talking to the gas pedal.’ She

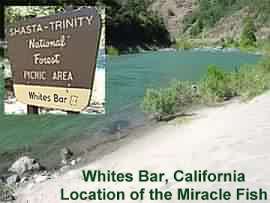

licked his face, and down the old highway they rode, straight to White’s Bar.

The choicest fishing holes in the river were Hell Hole, and at White’s Bar, and

Shanan was familiar with the finest of them.

WITHOUT A MOMENT’S DELAY, Cathy wrapped dexterous fingers hastily around her

fishing pole, leaped agilely from the station wagon, and began hurrying upriver

from the Bar, where she favored her luck among the jutting river boulders.

Shanan, on the contrary, and after yelling, “Honey! Keep your feet steady on

those boulders! They got the dam open again for the salmon, and the water’s

brutal!” favored a past-tested excellent and sandy spot just west of the

enormous ledge of exposed bedrock and beat a direct path to that part of the

shoreline. Amy, smiling in the run, peering back over her shoulder toward

daddy, running ahead and sidestepping nimbly, dodged brush and trees as she

pawed her way over loose cobbles and gravels. Grabbing a stick with her mouth,

she teased Shanan as they scurried to the river. He threw it about seventy-six

miles, for he had serious fishing to do, and Anxiety was accompanying his

hunger as he reached the bank of the swift-rolling Trinity.

Snapping a red-tipped Super-Duper

fishing lure onto his line, he paused, holding the upper shaft of his pole between his clasped hands, the butt resting on the sand at his feet. “Please,

dear Lord and dear God,” he prayed, “we’re so hungry, and we really do need a frying pan full of fish tonight.

Please help us fill our plates. Thank you,

Jesus. Amen.”

He raised his pole silently

into the air above his head. On his first cast, the line jerked as fast as the

lure hit the water, and he reeled

in a baby trout. “Durn near a minner! Sheesh!” he humored to

the fish. “Did you tell your mommy you were going for a swim?”

Shanan’s worldly mind ruled, and

judging this trout just a wee undersized, he tossed it back into the

river. “I’ll get you next year,” he quipped conventionally as he threw

his angle in search for a more impressive supper.

Sixty-plus prayer-accompanied

casts had spun themselves out from rod and reel, with no finny returns

whatsoever, when a flash cognizance suddenly launched him into shock-factor

ten, flipping him into a virtual panic. Throwing his pole quickly behind him and against a sloping bank of sand, he

joined his hands together tightly, and crushed

his eyelids shut.

“Oh…dear Lord…oh dear God.

Oh…my God! Please, God! Please forgive me,” he prayed. “I’m so dumb. You gave

me a fish on my first cast, and I threw her back. I prayed for that fish! Oh,

Jesus Lord, I threw back the first fish you gave me! God, I’m sorry!” he bawled. “Am I a bloomin’ idiot? You gave me what I asked

for, and I wasn’t satisfied…!”

This mortal, now veiled in

unconquerable falling tears, pleaded for tender mercy from the Almighty on

high. The warming sun had escaped completely behind the lofty,

purple majesties; abrupt dusk and the air

suddenly breezed their persuasions from a far colder realm; darkness was painting the eminent firs in

their height; and a shriveling stomach was

crying piteously for benevolence.

In a wretched straggle, he

retrieved his pole from off the indifferent ground, and began casting its line sorrowfully into the tumbling whispers of the Trinity. His humbled immodesty

was no longer strong enough to support his head, it nodded in the task, and his

ears had all but closed to the cool environment.

SHANAN SPIED CATHY,

from the corners of his vigilant eyes. She was walking speedily toward him,

guiding her steps carefully across the

massive lane of bedrock. Amy eagerly wagged her tail and, with a big

smile, greeted Cathy.

“How’d you do?” Shanan

hollered as she approached.

“Zip! How’d you do?”

“Thirteen!”

While driving back to the trailer, he raved and raved excitedly,

describing his entire experience: the baby fish he threw back, the praying. “And after I prayed, you know the

number of casts I had to make

to get these thirteen fish?” —Five fish was the legal limit—Cathy just sat with her elbow resting upon the window’s lower trim. “Fifteen!” he exploded.

“Thirteen fish in fifteen casts! The same

number as the apostles, I think. Is this awesome?” Shortly after the hungry pair and Amy—who was

always hungry—had arrived

home, the well-seasoned cast-iron frying pan

found itself filled with the freshest of mouthwatering trout; and four boiled potatoes were now

sitting beside the fish. Shanan had gone to a

neighbor and mooched the taters, but was exceedingly thrilled he had not

asked the Lord for help in

landing a job, only to reject a broom.

†