Click here to return to Home Page

CHAPTER EIGHT

YEAR 1971

SYRACUSE, NEW YORK

TIME, IT WAS SAID, HEALS, and for the past five years, Shanan had tried a gamut of

easier-said-than-done golden-touch-ping-instant-profit gimmicks: painting

pictures, sculpturing in a variety of media, and scores of other inventions and

ventures he felt qualified enough to conquer, including playing a frisky piano.

Beaten callously out of his ideas by large and unscrupulous corporations, or

finding no demand for his various talents in Syracuse (a city Shanan believed

could only be brought back to its once promising life by removing the stake of

sightlessness from its parsimonious heart), each after the next, he abandoned

his whims casually to their seemingly predestined inevitabilities and moved

happy-go-providentially on to his next project, our Mr. Gestalt’s next

horizonless hope.

BY MANHOOD, Shanan had outgrown all of his allergies, but the

grassless jungle of inner city now habitually held the bulk of his safaris. He

shot pool for $, bummed the downtown clubs, often getting drunk or in trouble,

and still hung with those loose babes of toy land. In deep depression and

steaming confusion, no more than a week after he was sealed in holy matrimony,

he had thrown his wedding

ring into the depths of Onondaga Lake. Shanan

was a reckless, seriously perplexed young man.

Nonetheless, but postdating

another interminable period of choice: abstinence from remunerative labor, he did land a

position delivering pizzas on and off for a

man named Goody, whose brother in those days was chief of the political and

executive committee of Syracuse. Which moves me to mention (concerning the chief of the political and executive committee of Syracuse), that during one evening of cheesy

deliveries, sunset having spread its dusky

mantle over the city an hour ago, Shanan, for driving without lights, was

stopped by a city police officer. The pizza deliverer had forgotten “…for three

lousy seconds,” —Shanan, please— to turn his automobile lights on as he pulled away from a curb

and had not driven a

hundred feet before the officer “…lurking in the shadows,” —Shanan—! stopped him.

In the midst of a light

apology, Shanan hesitated not to drop evidence that he was making deliveries

for Goody’s Pizza. This untimely name-drop provoked the officer—who

snapped his head forward an inch instantaneously—who reached immediately for

his pen and a thick book of tickets.

“Well,” Shanan lamented out

loud to himself, but certainly out loud, sensing a vapor of animosity exuding

itself suddenly from the pores of the police officer at hearing the name of his

superior’s brother, Goody, the brother of the chief of the political and executive committee of Syracuse,

whom the officer apparently disliked, “there

goes that sixteen bucks!”

“What do you mean,” the

officer trailed inquisitively, eyes rising and narrowing curiously toward Shanan, “‘…there goes that sixteen bucks’?”

“I told Goody that if I ever got a

ticket while delivering pizzas for him, I’d

work for him one night for free.”

I am not all that certain

whether I have to relate to you the remainder of the above-mentioned confrontation; but when Shanan was satisfied he was safely out of earshot of the officer,

there fled a gleeful and melodious declaration from his grinning lips and into

the ticket.less, moonlit night: “I was born in this here

briar patch… !” !”

AIMLESS ENDEAVOR can run blindly for only so long, before tightwad Lady

Fate finally loosens her grip, and the day at last came in which Shanan was

allowed to run off with the pot of gold from the end of the old proverbial

color-dumper. Without going into endless details, let it simply suffice with

this: He conceived and began a professional maid service from which he

subcontracted women to clean houses.

From its amateurish inception, business thrived; and

the instant and rapidly increasing volume of clients was nearly impossible to

handle. Maid services were a virtual myth in the U.S.A., in those days, and

residential demand for domestics was enormous. Now, a fortune was in the

making, and Shanan prospered as a king.

Nevertheless, in spite of his

outward success, this particular king had a couple of serious problems: He

squandered the money carelessly and nearly as fast as he raked it in; and,

night after night, extremely uninhibited and absolutely void of conscience

toward family or family

responsibilities, he would find himself in a house or apartment of a random female employee. Temptations took him without the slightest

resistance. Shanan was a weak-willed, mindless

adulterer who had no idea he was an adult.

A peculiar quirk, however, with which

he was casually familiar since childhood,

followed him incessantly. Every time he would engage himself in something wrong or

not a hundred percent on the up-and-up, a rather noticeable event would infect

the peace in his life. A stranger, or a dark force he could not see, would get

in the way of his activities constantly. He would lose a watch, break a

favorite tool, suffer an automobile accident, a friend would hurt his feelings,

or Shanan would come down with the flu, or cut himself; and these untimely events constantly insinuated a severe

and calculated precision.

The Eye-for-an-Eye Entity regularly

collected His due, and Shanan knew this.

Unfortunately, not paying earnest attention to these potentially equitable

affairs, his freewheeling conscience would deny their sundry coincidences

perpetually, he would find himself loosed from the perilous snare of his last judgmental engagement, and

jitterbug merrily on his way, yet doing whatever he pleased—an hour or so before the next throttling from the

unseen Administrator, often a half a second.

Tribulation

and anguish,

upon

every soul of man that doeth evil,

of

the Jew first, and also of the Gentile

YEAR 1972

SHANAN HAD TOLERATED the religious mystery of married-life for eight emotionally

wearying years; but, consequential to mismanagement and getting himself tangled

too often with his pretty employettes, and having heard the words “I love you”

from his wife on only eight depressing occurrences—six of

which he alleges he had to beseech her to tell him—leaving

two occurrences questionable—he decided to leave home.

He had often and sincerely pleaded with Ethel: “Let’s

move from this town. Let’s go to California. Let’s go to Florida. I can open a

business in Florida.” He had tried this approach many times, but at each

request, Ethel’s response was the same: “My family is here. My friends are here

in Syracuse.” Shanan forever wondered if he was actually included among her

family, or her friends: Why is it I don’t come first instead of her friends?

HOLD EVERYTHING! —Wait a minute here! If this droning history is looming too

melodramatically for you readers as it is for me at this moment, let me

patronize our common weariness and exclude these partial realities and simply say—Shanan wanted to leave to begin with and packed his bags! He was hardly

ever at home, anyway. The guy was a bum! His six-year-old daughter, Annette,

was the last of his family to see him (wife Ethel, Annette’s brother, Buddy,

and sister, Lizzy, yet asleep upstairs). Last

to see him because Annette happened to wander downstairs very early in the

morning, and caught him in a half-dark kitchen on the day he skipped. Oh, how I

hate excuses!

“IT’S OKAY you’re leaving, daddy,”

his daughter sighed, not realizing exactly why, “I understand.”

Shanan thought he was

listening to the infinite wisdom of his Grandmother Bin, and his little girl’s

words of goodbye have lingered in his mind to this day, and may for eternity.

He bent over and kissed her cheek tenderly—and exited.

A couple of his “devoted” chauffeurs

drove him to Binghamton, New York, where he boarded a Greyhound Bus to

Florida. Shanan was a deserting—deadbeat!

NOW LET US GET BACK ON THE TRACK:

FLORIDA

IN THE SUNNY AND SANDY CITY

OF DAYTONA BEACH, he bought a used,

flat robin’s-egg-blue Mercury station wagon (a near relative to something used

to convey George Washington through the Revolutionary War) and, ere he had

filled its gaping mouth with low-octane gasoline, began his second maid

service. The young women were just as sociable and free-spirited as those in

Syracuse, and Shanan was rarely, if ever, lonely.

Moved by an impetuous

infatuation, however, in his new and unfettered surroundings, within the space

of a month and a half, Shanan married again. The only sour note in this touchy,

may I say, madrigal: He had not divorced Ethel, and the woman he married

had known this well-before the polygamous knot was tied. Nonetheless, they were

both tremendously happy. The nice part of this unconventional situation: His new little barefoot bride, Helen, that American Beauty, that siren of femme

fatales, who danced in his mind, sang to his heart, teased his soul, and

rocked his boat, spoke the words “I love you,” —and, frequently!

The old eye-for-an-eye syndrome,

however, was still following Shanan, and after

eight extremely complicated months of that marriage, he annulled and was

“ On the road again... On the road again...  ” ”

Footnote:

Seedy years grew

into a trunk of a lumbering decade or so, and a

day arrived wherein Shanan deduced for himself that marrying after spending only a short span of

time with a prospective partner was not unlike

finding oneself drinking desperately from a pool of water in the middle of a

parched desert…before opening one’s eyes and noticing all the bones strewed

around it.

YEAR 1973

ANOTHER PET PLEASURE of Mr. Bin’s was hitchhiking: the roughing it; washing his

dusty hands and face in creeks or from the dew of wet morning grasses; and,

every so often, the sheer enjoyment of walking through entire major cities by

virtue of their innumerable charitable drivers. Furthermore, sleeping under

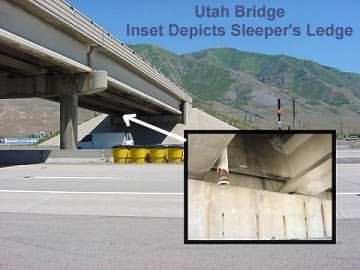

steel and concrete bridges, in storm drains, or fields, undeniably increased

his love for the emancipation from the regulated, the normal, and the municipally disciplined.

Contrary to the above, though, several persons who had

given Shanan a lift had also bought him an unsolicited bus ticket to aid him in

finishing his trip—to wherever. On one state-hopping excursion, three or four

years before he deserted to Florida, two days before Christmas, a man freshly

retired from the Navy, who had driven Shanan on an all-expenses-paid ride from

Las Vegas, Nevada, to Kansas City, Missouri, had, from an agency at the Kansas

City Airport, rented him—unsolicited by Shanan—a new car: a golden Rambler

Ambassador, which guaranteed a speedy finale to his journey, and allowed him to

be with his family for the holidays. On many other wayfaring globe-trots,

churches (though not all) were also charitable and had helped him with a can of

food or two, or, if he was driving, three or more dollars’ worth of gasoline or

of other petroleum products. Conversely, but only on exceptionally rare

occasions, days would pass between rides, which would give Shanan hours to

meditate on life in general: These lousy slugs!

On another of Shanan’s uncountable

hitchhiking adventures (and I will try to be as brief as possible), a Richmond,

Virginia, city police officer, who had temporarily lost the will to smile,

possibly not temporarily, arrested Shanan for standing at the beginning of a

ramp leading down to an interstate highway (apparently not a freeway)

within the city limits. As the officer was transporting his newly captured

interstate prisoner to the city jail, he further arrested a tall, young man in

a cowboy hat, who was hiking also—on the highway—and placed him with

Shanan in the back seat of the squad car.

SHANAN WAS STANDING

stiffly with his fellow transgressor at the front desk of the process of

destiny, stone-broke and starving for something he used to know as food. Poor

chap had not eaten for two whole days.

“The fine is twenty-five

dollars, fellas,” the clerk announced.

Without the least bit of

hesitation, the tall, young hitchhiker removed his shoe, reached to the sole of

his musty sock, drew forth a small wad of legal tender, and, showing no facial

distress whatever, paid the required ransom, and was escorted to an

exit. Shanan was now standing before the desk, naked of humility, but not of

discourtesy. “When’s supper, please?”

“You’ll have to face the

toughest judge in town if you don’t pay,” the clerk stressed: “He crucifies

hitchhikers.”

“Let me put it this way,

sir,” Shanan reiterated calmly: “What are—we—having for supper? Sir, please don’t laugh at me like

that.” As I mentioned, he was starving!

THE FOLLOWING MORNING, slightly apprehensive but filled with a cup of last-night’s

watered-down coffee, and four bologna sandwiches (three inmates threw him their

sandwich but drank their coffee) and that morning’s watered-down coffee

breakfast, in City Court, Shanan found himself standing nervously before the

Honorable Judge Maurice.

“You th’ hitchhahker?”

“Yas, Yo Honor,” Shanan

confessed, trying to blend himself cordially into his southern environment.

“Where y’ hitchhahkin’ to?”

“Daytona Beach.”

“What’s in Daytona Beach?”

“Mah home, Yo Honah. Ah’m

tran t’ git home.

“Well—boy…”

Judge Maurice grinned, “I’ll just help you get to Daytona Beach,” and he stood, tipping a might forward, and

reached beneath his long, black robe.

The judge rose composedly

from his well-cushioned seat, and held out his hand over the bench toward the

elated expression of his hitching guest. “Here’s two dollahs for a bus ride to

the outskirts of Richmond. Y’ cain’t hitchhahk on Ninety-fahv. Don’t get caught

on Ninety-fahv again, or I’ll throw you to th’ turnkey and forget I ever saw

you.”

Utterly bewildered, Shanan

accepted the money. “Thank you, Yo Honah! An’ A’h would jess lahk t’ say—”

“Show this boy where th’ bus

station is,” Judge Maurice ordered, signaling the bailiff.

The judge recaptured Shanan’s attention; Shanan’s

stare went from the bailiff back to Judge Maurice and captured every word he

said. “Th’ bus’ll take you to Route Eighty-fahv South. Nobody will bother you

on Route Eighty-fahv. You may hitchhahk to Daytona, on that highway….”

As Shanan was eliminating himself from the charitable

court, he glanced back to the judge for one last look, and while doing so

noticed, surprisingly, the tall, young hitchhiker in a cowboy hat, who was just

being led into the court to wait for the man behind the lectern to judge the

totally disregarded and lawless reentry onto highway Ninety-five.

SHANAN did as instructed: boarded an outbound bus, sat himself

complaisantly next to an elderly woman; and, after alighting at the appointed

destination, strode triumphantly, splattered by a wide range of blissful

sunbeams, to the entrance of the ramp to Eighty-five south, whereat he spied a

lone dollar bill lying amid the grasses on the side of the road: Food! Real

food! Three cheeseburgers at Burger Binge!

Near to the end of the

following year, in far better financial shape, Shanan licked and pasted a

postage stamp onto a Virginia-bound letter and mailed the two-dollar loan along

with a nice note of thanks to Judge Maurice—believe it or not.

NORMAN, ARKANSAS

NOW, SHANAN’S FIERY

ANNULMENT was concluded. He had traded

his second maid service for a handful of money, and gave his station wagon to a

friend of like transitory temperament. His mind’s eye now visualizing The Great

Freebie—Outdoors—Shanan grasped his briefcase, filled with writing

material and poems, an old leather gaucho hat, bound a three-quarter bedroll

and a green and yellow rain parka tightly into a bundle, including fishing line

and hooks; and, jacketing himself against the cool of the season,

hitchhiked—subsequent to the above vehicle transaction—into the lush, sweet

hills of west-central Arkansas, to fish for both fish and for inspiration to

write his poems. He considered his poems very personal—and mandatory, and could

not care less whether his spelling or punctuation marks were correct: placing

them properly was by no means important to him. Possessing quite a natural gift

toward evolutionary poetry, he simply wrote miles of words and loved every mile he

wrote. At the same time, however, if I may say, a body might truly appreciate

his written works if a body were able to comprehend precisely where the commas

were supposed to fall. Shanan was a free spirit, indeed he was; and, where he

would roam from Arkansas, who knew, who cared.

The man was married to his

Freedom—indelibly. He would walk with her, talk with her, live with her; and,

although the Wind was his friend, and he cherished her, he would sing

perpetually and effervescently into Freedom’s bosom: “ Long live my wife... Long live my wife...  ” ”

The day was golden-sunny with skies bespeckled of

cottony white clouds when the pickup truck driver dropped Shanan off just

outside of Norman, Arkansas, on a state highway southeast of the village. A

spirit-motivating and exploring walk led him off the highway, and he ambled a

half-mile of country road into a forested area of Caddo Mountain. Having

selected what appeared to be a semi-wilderness but habitable campsite at the

base of a woodland hill, flowered beautifully and located openly near the edge

of a meandering, blue and crystal-clear creek, he assembled a waist-high

lean-to, tying to sturdy but leafless branches the green and yellow rain parka,

beneath which to place his three-quarter bedroll, to accommodate his hours of

sleep. With his residence established, and contemplating dinner, he parted

loose pine needles found at the base of a lofty fir tree, grabbed and pinned a

squirming red worm onto a fishhook tied to the end of a length of fish line,

using a tiny stone for its sinker. He tossed the line haphazardly here and

there into the creek and thereby hauled in a couple of gorgeous trout and

strung them into the water, tying them from a leaf-barren stalk growing near

the shore, which stalk, in consequence to the hanging, began to mimic a busy

fishing rod.

A rolling and

darkening overcast had spoiled the brightness of his day prematurely

and, though the hours had not fully voyaged themselves tranquilly into the

dusk, he was no longer able to see well enough to write, or to cook his fish.

Feeling a nap was in order,

he laid himself down beneath his “Motel Lean-To,” gave the nap a date for

tomorrow, tried to write two poems, handled a little something wrong, and

settled early into his cardboard-thin, three-quarter sleeping bag, hungry for a

night’s sleep.

A MEASURELESS invasion of thunder and an unbridled display of electrical

bolts accompanied a monstrous downpour of sheets of lashing rain and a menacing

drove of howling and careening winds. Shanan awoke in shuddering amazement,

reasoned, and, in a bat of an eyelid, raised himself to his elbow, extended his

arm, and felt the foot of his modest sleeping bag. The inside lining was now

sopping wet. Except for the repeated blasts of lightning bursting their fierce,

burning veins throughout the bubbling and buckling clouds of the firmament, the

storm-wracked night was altogether as black as the sins of Satan. Shanan hustled a peek from under a hem of the parka and, between

the supercharged electrodynamics, could discern, but barely, that the shallow

stream, now only inches from his “motel?” was bloating to a river of rage,

heartless and unrepentantly, and its shoreline shrubs and jutting rocks could

be discerned no more.

The serene mountain evening was fretfully cool to

begin with, and Shanan, as he retired, had refrained from shedding his jeans

and shirt. He needed merely to throw on his shoes, kneel, and leap away from

his whiplashing shelter.

Thunder was roaring itself into colossal fits,

stomping its iron boots, and dragging its ponderous chains across miles of

boiling clouds. Lightning was furious, blazing, unending, but an effective

guide as Shanan hastened to scope out the wooded surroundings for a higher

place to reorganize his gear. His scanning efforts, however, proved an

impossible plan; and, by the time he had stumbled half-blindly back to his

waterlogged site, his waterlogged sleeping bag was disappearing. Turbulent

waves (in concert with lightning flashes illuminating their foaming heads,

creating an angry illusion of curling and tumbling eyelids of dreamlike molten eyes)

were diving into blackness and popping up mockingly hither and yon in witness

to the night’s inundation and were now clawing the sleeping bag swiftly into

the rising creek.

He rescued his bag quickly, untied, and snatched the

rain parka off the leafless limbs he had earlier draped it across to protect

his belongings. He flipped his old leather gaucho hat to his head, threw the

parka over himself, and, after infolding the rain- and creek-soaked sleeping

bag beneath the parka, grabbed and added to the bundle his socks, briefcase,

and jacket. Forsaking the rest of his meager gear, he bolted again for

elevation and clambered precariously for the nearest road. When he had plodded

ten more sloshing steps, through a tangled array of buffeting overgrowth, he

paused, thought, and flung his poem-filled briefcase aggressively into a

distant patch of brush. Poems come; poems go; I can replace them, pacified his

agitated mind. Canceling the thought of a road, he turned and began trudging

slowly up a steep and slippery and gray-mudded bank toward an ankle-deep,

gray-mudded-but-wide path. He was bent as beldam and drenched to the joints of

his skinny bones, but the fearsome lightning perpetually scattered the darkness

shrouding the untamed night, allowing a retarded but steady gate down the

middle of the long and winding path.

Winds of fury were moaning like a pathetic ten-headed

wolf caught in a woodsman’s trap, bellowing pitifully into a moonless sky for

the deliverance of deceived paws. The ever-swelling ground exhibited an

illusion of heaving itself upward, sinking, rising, sinking, rising, as if

respiring and choking between the flashes of the breathtaking Fire of God, but

was an absolute blessing in a reflecting disguise and proved easier to navigate

than Shanan at first expected it would be. “But the winds, these unyielding

winds, God, Lord, ARE SHRIEKING!” he realized suddenly and loudly, as he bowed

and hunched his shoulders and struggled the plunging of his muddy shoes into

the bulging, gray mud, out of the bulging, gray mud, into the bulging, gray

mud, the color of his socks now equal to that of the mire through which he

tramped.

Pushing stubbornly against

their legion of thick howls, he dove squint-eyed into brutal squall after

tempestuously vicious squall, the pelting deluge of rain battering heavily

against his cascading face. Each individual step, as far as dripping Shanan was

now concerned, only increased dubious chances of seeing another

tomorrow. Unsheathed lightning was exploding as low as the wildly spiraling

treetops. The vicious bombardment was so abundant, Shanan cried aloud, “If you

want to kill me, God, it’s okay; I sure have done my share of rotten stuff in

my life. And you know I’m half-sorry for everything—Oh, my God! This is

incredible…this is intense—Gads!” he reevaluated in a whisper, “God really could kill me, if he wanted to kill me,”; but quite unexpectedly, the voice from within began to

speak. “Fear not, Shanan, for

from the first you set your heart to chasten yourself before your God, your

words were heard, and I am here for your words.”

Not until this night had

Shanan ever experienced blasts of heavenly flame so close to the Earth—and

of this, of this unusual quantity; but after the voice spoke, fear was cast

from Shanan’s soul, and he was left with just determination: Get to the main

road; the lightning will stop; the wrath of God will cease; Jesus loves me…Jesus

loves me… Thus, with these new and encouraging thoughts racing through his

rekindled mind, he practically ran to the welcoming state highway—a shock

revelation, as orientation, time, and distance had thoroughly vanished from

Shanan’s inner map, clock, and pedometer.

The lightning bursts did seem

to diminish, the winds in like manner, yet the rain was still unleashing its

fierce torrents. As Shanan slit-eyed and laboriously slaved himself toward the

north, a shine, and a near deafening reverberation of thunder hammered into his

ears, preceding a tremendous spray of blazing lightning (not unlike that of a

brilliantly glowing, leafless oak tree turned upside down, branches and twigs

iced, electrified, and threading themselves rapidly in every downward direction)

and spread its powerful flash over the lofty steeple of a lonely, white country church silhouetting itself across a vast and un-mowed pasture.

This was a sign, a sign, and

it verily beckoned him. Leaping over a barbed wire fence and scrambling across

a drowning field of knee-high grasses, furrows, and tire ruts, he quickly found

himself standing speechlessly and shaking, staring desperately into the front

of that restful frame church. The forceful gusts intensified again and

propelled him vigorously toward its front entry.

A SIMPLE TWO-STORY HOUSE was the only nearby dwelling, directly behind Shanan and

across the narrow asphalt road from where he now stood; and, as he promptly and

craftily observed, not the faintest glimmer of luminosity was leaking through

its windows (the two-way eyes of the house). Shanan, an optimistic morale lifting

itself courageously by the inch, light-footed the five creaking stairs to the

slippery deck of the church and pressed a thumb onto the motionless brass tongue

protruding tastefully from the handle of the French door to the right. The door

creaked open. Shanan hopped nimbly over its threshold—outbursts of thunder

camouflaging the stamping off of his shoes—but half-noticed a sliver of yellow

light betraying a length of white door casing in a shadowy hallway. Cognizance

of the yellow light was not yet projecting itself fully into Shanan’s

momentarily insane intellect; and, soaked to the bone, from his drooping

leather hat, to his field-washed shoes, he shut the front door slowly behind

himself and wasted minimal effort in completing his entering of the church. Not

a square centimeter of his flesh was dry, including the inside of his parka.

Shanan, utterly fatigued and not caring for further

physical exertion, and realizing he was now standing in the narthex of the

church, dropped his bundle of belongings from beneath the parka listlessly to

the floor, unpacked, and hung his sodden effects languidly over an array of

archaic bronze coat hooks on a narthex wall. Succeeding these necessary

efforts, he, shaking his head, blinking his eyes, attempting to adjust his

sight to the inner darkness, peered searchingly around and into the sanctuary.

Satisfied with the positive evolving of his vision, he stripped progressively

to his flesh, hung his clothes over a couple of more hooks and, naked as the

truth, found a box of rags in a corner of the narthex, and toweled himself as

efficiently as he could.

God had provided guest Shanan

a place in which to relax his battered nerves. Semi-dry at last, our now

salvaged but teetering (like a toy top teetering into gravitational pull)

sojourner rejoiced within himself: Gee, without all that lightning, I might

have gotten lost. And I certainly wouldn’t have found my way to this church.

Thank you, Lord…!

Finally and thankfully

relieved of his saturated burdens, and suddenly remembering that yellow sliver

of light, he deemed it a wiser than wise idea to inspect his provisional

quarters: Nuts as it sounds, others may be here. Feeling his way cautiously

through the sanctuary and into the hallway from which the sliver of light was

emanating, he peeked in and crept noiselessly through the doorway of a tiny

office, not a mortal present, a plastic nightlight emitting a moon-glow ambience

throughout the setting. Content he was alone, as he brailled his fingers

through the drawers of the only desk therein: prospector genes, I imagine, he

fumbled onto a glass canning jar with a goodly number of coins rattling within,

scooped a handful for himself (leaving the majority of the coins in the jar),

tucked the jar quietly into its original position in the drawer, exited

stealthily from the office, and hush-footed himself back into the mute

sanctuary.

He had fished but two dollars

in change. How about that: Not only was a slight bit of change left in that

poor little jar, a slight bit of change could likewise be found in poor Shanan.

He had allowed the bulk of the money to remain. A gnat of a change in him, yes;

nevertheless, a change.

Two dollars jingled evenly

divided into the front pockets of his hanging jeans: I’ll pay this back in the

future, he pondered. Of course, this ‘I’ll pay them back in the future’ was a

regular phrase with him, but what it meant this time was left to be seen.

His weary eyes had grown

better accustomed to the dim in his new but temporary dwelling. An obsolete

upright piano resting to the left of a tall and oak-stained lectern beckoned

silently, and he walked to it, and settled his unclothed body comfortably upon

a timeworn, upholstered bench. His lips formed a voiceless prayer to God; and,

remembering his childhood, he began to play The Old Rugged Cross,

lightly upon the keys.

Outside the church, the rain

had tuned itself to more of a hiss than a drizzle, the lightning had passed

over and into an adjacent county, and the land about the church was finally at

rest, thunder now echoing forgiving sentiments softly, as it raced heavenward

over the same adjacent county, heavenward for the next command. Inside the

church, the hushed, ringing sounds whispering their wistful melodies from the

tinny-voiced piano could not escape the sanctuary.

As Shanan played the archaic

hymn, fond memories of mother and grandmother began rising softly within his reflective

heart. Although his grandmother had attended church only on Easters and

Christmases, had not made herself subject to books on child rearing, she had

coached Shanan through many of his prayers—rarely, if ever, suggested in books

on child rearing. Remembering church with his mother was a natural, as she had

faithfully, and on a weekly basis, delivered her children to their Sunday

school. She herself would often attend the Sunday Service; and, when she did,

young Shanan would be sitting to her immediate left, holding her hand.

Notwithstanding the closeness of the seating arrangement to her boy, she would

usually have to say, no less than nine times during a Service, “Cut your

fiddling, and sit still.” Now, contrary to his youth, here he sat, still, alone,

and peaceful in a church and at a church piano. The inherent love for his

mother and grandmother increased as Shanan played, him cherishing a medley of

those reminiscent memories of yesteryear; and, as he exercised his fingers

carefully across the yellowed, ivory keys, he wept.

At last, consuming enough of

his nostalgic music and sharing it with the witnessing walls, he retired naked

and exhausted into his

soggy sleeping bag, now laid upon the tongue-and-groove floor in the humble narthex. He discovered peculiar yet

comfortable warmth existing between his soggy blanket, and he tumbled in peace, immersing himself into his

gratifying, totally worn out, but carefree dreams.

AT THE BREAK OF DAY, Shanan opened his big, wide eyes to a multi-hued wall the radiant sun was painting delightfully as it passed itself boldly through the assemblage of colored panes of rippled stained glass, their colors bleeding into the rays for a decorative ride to the narthex interior. With a magnificent feeling of regained freedom, and the weight of the night before, removed lovingly from his shoulders, he wriggled himself from his soggy sack, climbed deftly into his soggy clothes, bundled his soggy belongings, and cracked open

the left French door—just a wee bit. He squinted into the brightness the day was offering at no charge, adjusted his sight, and peeked to see if the neighborhood was unpeopled. Satisfied by the hushed surroundings, Shanan

departed with his soggy gear tied close together beneath his arms, and, with his forefingers, stirred the coins within his soggy pockets.

The Sun in all her

resplendent and spatial glory was shining her silent, cloudless song of life

into the living blues of Heaven’s beginning, and this unruffled display of

Earthly eternity soothed Shanan’s soul. The church door creaked itself closed

behind him, with a light click of the tumbler, and Shanan scurried his

happy-go-seemingly-lucky feet down the steps to the inviting sidewalk.

Forgetting completely the violent night before, he lifted his face into the

beaming warmth and made a quick stride to the corner. Hooking himself to the

right, he headed merrily off toward the now appealing South—just

a-whistl’n and a-sing’n and a-struttin’ down that good old country road: “ To the drier we will go! To the drier we will go!  To the drier we will go! To the drier we will go!  Hi ho, the daddyo, to the drier we will go. Hi ho, the daddyo, to the drier we will go.  ” ”

YEAR 1974

TUNIS, TUNISIA

THE ARAB LEAGUE had finally recognized the Palestinian Liberation

Organization as the sovereign representative of the Palestinian Arabs. Arafat

plowed the international bureaucratic fields and won applauding recognition for

his organization. He made every conceivable effort to delete his terrorist

reflection, exchanging his uncivilized stripes for the profile of a reasonable

statesman.

†

Click here for next chapter

Click here to return to Home Page

|